The Electoral College: How the System is Rigged and How to Change It

Full database of sources on the Trump Election | Database entries on the electoral college

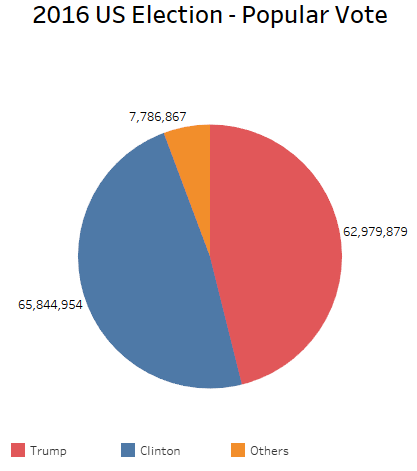

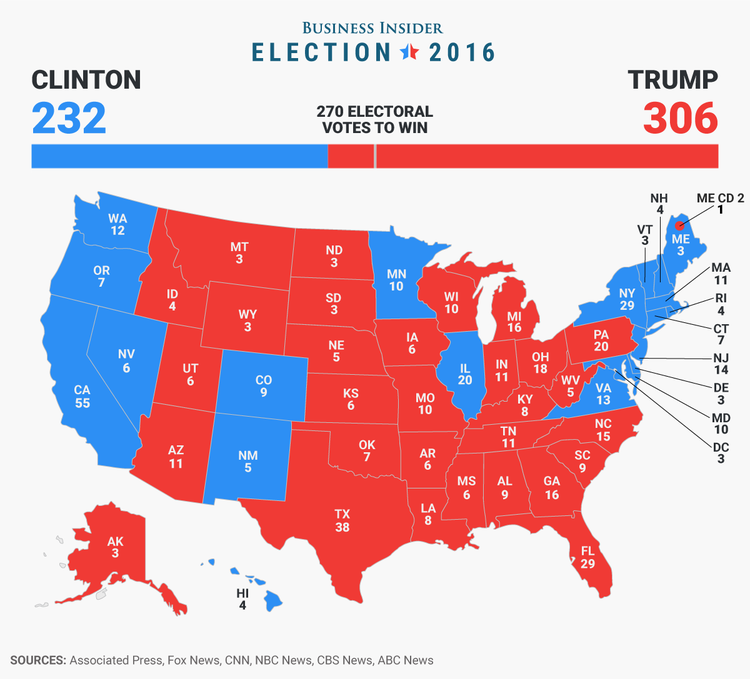

The most direct explanation for the US presidential election outcome in 2016 is the Electoral College. Democrat Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by almost 3 million votes, or 2.1 percent of the total. Republican Donald Trump, however, won the Electoral College, taking 306 of the 538 electoral votes. He did so by winning three key battleground states – Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin – by a tiny margin of 77,744 votes, or just over one-twentieth of one percent of the total votes cast nationwide.

If the United States chose presidents by popular vote rather than the Electoral College, and if the popular vote had fallen along the lines that it did in the 2016 election, Trump would not be president. The phenomenon of a president elected by a minority of voters, as George W. Bush also was in 2000, would have been ruled out.

It is not certain that the outcome would have been different if the Electoral College did not exist, since campaign strategists on both sides would have taken that into account and fewer resources would have been allocated to battleground states. But it is now widely recognized that the Electoral College system systematically advantages Republicans because of its disproportionate weighting of rural states with fewer voters and smaller non-white populations.

The Electoral College, made up of electors chosen by the states in proportion to their representation in Congress, is based on the Constitution. It reflects a compromise in which the framers, in 1787, gave more electoral power to the Southern slaveholding states than those states would have had in a system of direct popular elections (see a clear short video explanation here). By counting the total population of states to allocate representation in the House of Representatives and in the Electoral College, with each slave counted as 3/5 of a person, the system gave greater representation to the Southern states, which had fewer voters but more people.

The addition of more states, demographic changes, the abolition of slavery in 1863, and several amendments have changed the way Electoral College votes are apportioned, but the basic institution has remained in place. Although the District of Columbia does not have voting representation in Congress, it was also granted 3 Electoral College votes in 1961 by the 23rd amendment, the same number as seven states having only one member in the House of Representatives due to their small populations.

Amending the Constitution to abolish the Electoral College is generally dismissed as impractical. But there is a way to make the body irrelevant, because the Constitution grants states full authority to determine how they allocate their electoral votes. The proposed National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/) would take advantage of that state prerogative to achieve the same outcome as a direct, popular election. This proposal has already gained the support of states with 172 electoral votes and can go into effect when states with 98 more electoral votes approve.

A skewed system: How does it work now?

How can the US presidency be captured by a minority? The answer lies partly in the structural bias of the Electoral College, and the US political system more broadly. The US Congress has two chambers, the Senate and the House. Each state’s delegation to the House is based on that state’s population. But each state, large or small, has the same number of senators: two. Wyoming’s 580,000 residents get two senators, and California’s 40 million residents also get two senators. This means that the balance of power in the Senate disproportionately favors states with small populations.

This disproportion is mirrored in the Electoral College, the body that actually elects the president. Each of the 50 states gets two electors for its two senators, plus additional electors based on its number of House representatives. All states except two allocate their electoral votes on a winner-take-all basis. So the winner of the popular vote in a state gets all of that state’s electoral votes, even if the vote was very close. Because it’s based in part on Senate representation, the Electoral College gives more voice to voters from small-population states, just as the Senate does. Thus Wyoming, a rural, sparsely populated state, has three Electoral College votes – one for every 82,000 or so voters in the state. By comparison, California, with its big cities and huge population, has 55 Electoral College votes – one for every 218,000 voters. So a Wyoming voter has almost three times as much clout in the Electoral College as a California voter.

Over the past half century, many rural states in the South, Midwest, and West, whose voters are predominantly white, have become heavily Republican (“red” states). States that are more urban and diverse, mostly located on the coasts, tend to vote Democratic (“blue” states). This pattern dates back to the 1960s, when the Republican Party rolled out its “Southern strategy” aimed at attracting white voters through racial appeals. It has become even more marked in recent years.

What does all this mean for US politics?

- In presidential elections, the outcome is decided in a few states. In a handful of competitive “swing” states or “battleground” states, the race could go either way. Candidates visit these states frequently and spend millions in advertising to reach their voters. But most states are not battlegrounds: they are considered reliably red or blue, with the outcome of their vote a foregone conclusion. Presidential campaigns largely ignore voters in those states.

- Republican states have more weight in presidential elections. The rural, small- population states with greater weight in the Electoral College mainly vote Republican. This gives the Republican Party a built-in advantage when the Electoral College chooses a president.

- Republicans control the Senate. In the elections that determined the current Senate (2012, 2014, and 2016), 15 million more votes were cast for Democrats than for Republicans. But because of the systemic bias, conservative Republicans have kept control of the Senate and use their power to thwart laws and policies that a majority of the country favors. The Senate confirms the president’s cabinet appointments and – crucially – his nominees to sit on the Supreme Court. The Republican-controlled Senate refused even to consider President Obama’s Supreme Court nominee in 2016, and it is poised to confirm President Trump’s nominee in 2018.

- Republican control of statehouses helps entrench the system’s bias. As of mid-2018, Republicans control 32 of the 50 state legislatures. In states they control, Republican officials have used voter suppression laws and practices to prevent African Americans and Latinos from voting (since these groups tend to mainly vote Democratic). This has been central to Republican electoral strategy ever since the civil rights movement victories of the 1960s. State legislatures also draw the lines that determine how a state chooses its delegation to the US House. Republican state officials have used redistricting, or gerrymandering, to configure their House districts in such a way as to ensure continued Republican control.

What can be done?

Amending the Constitution to abolish the Electoral College is generally dismissed as impractical. But there is a way to make the body irrelevant, because the Constitution grants states full authority to determine how they allocate their electoral votes. The proposed National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/) would take advantage of that state prerogative to achieve the same outcome as a direct, popular election.

The plan works like this. Individual states pass legislation to allocate all their electoral votes on the basis of the national popular vote, with the proviso that the legislation will take effect once enough states have approved this option to provide at least 270 electoral votes. As of 2018, 11 states plus the District of Columbia have passed such laws (California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington). They have a total of 172 electoral votes, so their laws will take effect when states with 98 more electoral votes have passed equivalent laws.

For a short video explanation of this proposal, see here on Facebook. The New York Times editorial board, which has advocated reform of the Electoral College since 1936, also now supports theNational Popular Vote Interstate Compact.

In the past, polls have shown strong support among Americans for selecting a president by national popular vote. Unsurprisingly, however, support has dropped sharply among Republicans since the 2016 election. In the most recent polls, there is a narrow majority for a national popular vote of 49% against 47% who support the Electoral College. Support among Republicans for a national popular vote has dropped to only 19%, in contrast to 81% among Democrats.

The key to implementing this option is, of course, the state governments, and this highlights the importance of state legislative races in 2018. This “building from the ground up” strategy is the focus of the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee (http://www.dlcc.org/), as well as a host of progressive organizations that see the states as key to victories at the national level, including in the 2020 presidential election.

Database of sources

ArticlesBooks and Working Papers