No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000

Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr.

Published by Africa World Press.

home

|

No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000 |

Edited by William Minter, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr. Published by Africa World Press. |

|

An Unfinished Journey by William Minter The 1950s: Africa Solidarity Rising by Lisa Brock The 1960s: Making Connections by Mimi Edmunds

The 1970s: Expanding Networks by Joseph F. Jordan

The 1980s: The Anti-Apartheid Convergence by David Goodman

|

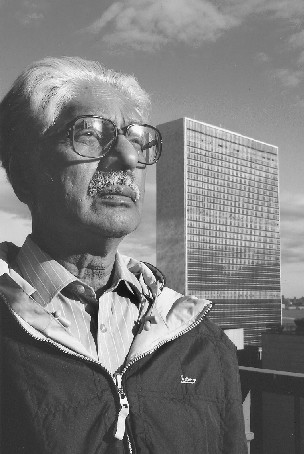

Featured TextThe following text is excerpted from No Easy Victories for web presentation on allAfrica.com and noeasyvictories.org. This text may be freely reproduced if credit is given to No Easy Victories. Please mention that the book is available from http://noeasyvictories.org and http://africaworldpressbooks.com. E. S. Reddy: Behind the Scenes at the United Nations

E. S. Reddy made the U.N. Centre Against Apartheid an indispensable resource for the

anti-apartheid movement. Coming to the United States from India in 1946, E. S. Reddy was both a witness to and an important participant in the international struggle to end apartheid in South Africa. He went to work for the United Nations Secretariat in 1949 and served there for 35 years. From 1963 to 1984 he was the U.N. official in charge of action against apartheid, first as principal secretary of the Special Committee Against Apartheid and then as director of the Centre against Apartheid. United Nations action both legitimated and was influenced by the momentum of popular mobilization against apartheid. Reddy was probably the most consistent and influential of the U.N. officials working behind the scenes, ensuring that the United Nations not only represented governments but also helped build bridges between liberation movements and their supporters in the United States and other countries. Inspired by his own country's struggle for independence, he first connected to Africa through the Council on African Affairs in New York. Later, when African countries gained influence at the United Nations, he was able to use his position in the Secretariat to work closely with the American Committee on Africa and Episcopal Churchmen for South Africa in New York, and with other groups around the United States and around the world. E. S. Reddy spoke with Lisa Brock in New York City on July 20, 2004.

E. S. ReddyI was already interested in the anti-apartheid movement in the 1940s, when the struggle in South Africa took on new forms and Indians and Africans were cooperating in the struggle. During the Second World War, the United States and Britain talked about four freedoms in the Atlantic Charter, but those freedoms didn't apply to India or South Africa. As Indians we were very much interested in South Africa, because a lot of Indians were there and they were treated as second-class citizens or worse. And of course Nehru was talking about South Africa, Gandhi was talking about South Africa and so on. I arrived in New York in 1946, shortly before the Indian passive resistance and the African mine labor strike in South Africa. I learned from a friend that there was a Council on African Affairs in New York with a library that got newspapers from South Africa. So I began to go to the council almost every week and look at the newspapers. That is how I met Dr. Alphaeus Hunton, a very fine man. He was head of research at the council at that time, later executive director. We became good friends. In June 1946, India complained to the United Nations about racial discrimination against Indians in South Africa and the matter was discussed in November and December of that year. A delegation led by Dr. A. B. Xuma, president-general of the African National Congress, came from South Africa to advise the Indian delegation and lobby the United Nations. Paul Robeson, who was chairman of the Council on African Affairs, hosted a reception for them and I met the delegation. The council organized a demonstration in front of the South African consulate in New York. I was in contact with the council, and took a group of Indian students to join the demonstration. When the Indian delegation came to the United Nations in '46 for the first time - the free Indian delegation - they said the main issues in the world for us are colonialism and racism. They were not interested in the Cold War. India felt very strongly about discrimination in South Africa, and also took up the question of South West Africa [Namibia]. It not only tried to get support from other countries, but tried to build up support from the public, especially in Britain and the United States. All those who supported India's freedom now began to support African freedom, because solidarity can easily be transferred when the basic issue is freedom. The people who were in the solidarity movement for South Africa in those early days were mostly the people who were in the solidarity movement with India. In 1952, after the African National Congress decided on the Defiance Campaign, India and some Asian and African countries got together and asked the United Nations to discuss the whole question of apartheid. By that time I was working in the U.N. Secretariat, and my boss called me in for a chat. He said, " Don't you think it's illegal to bring that up? It's an internal problem." So I said, " No, I don't think so. I think it's a matter of how you interpret the charter." Because you know when the U.N. charter was signed, the real India was not there. And we had a different attitude towards the charter than some of the Western countries; it's a psychological thing. He didn't like that at all. He said I was prejudiced, not objective. Supposedly U.N. staff should be objective, neutral and all that sort of thing. So he moved me from research on South Africa to the Middle East. The atmosphere in the U.N. was terrible for many years, until the sixties. It changed after many African countries became independent and joined the United Nations. Third World countries became a majority. So the situation was much better when the Special Committee Against Apartheid was established and I was appointed secretary. The Western countries refused to join the Special Committee. As a result, all the members and I thought alike. Not only were we against apartheid, but we supported the liberation struggle and opposed Western collaboration with South Africa. The members of the committee, who were delegates of governments, and I could work together as one team. That could not happen in other committees where the members were divided and the Secretariat was supposed to be neutral. Coming from India, with the influence of Gandhi and Nehru, I felt that we had a duty not only to get India's freedom, but to make sure that India's freedom would be the beginning of the end of colonialism. Rightly or wrongly, I had a feeling that I had not made enough sacrifice for India's freedom, so I should compensate by doing what I could for the rest of the colonies. That feeling was in the back of my mind. The real opportunity came when I was appointed secretary of the Committee against Apartheid in 1963. Other officials were not interested, as they felt the committee was worthless. I wanted to give the best I could and I did for more than 20 years. Soon after the committee was formed, we had a private meeting of the officers. I explained to them what I knew of the situation in South Africa and what I thought the committee and the United Nations could do. The chairman was Diallo Telli from Guinea, who later became secretary general of the Organization of African Unity. He liked my presentation, and said, " Look, Mr. Reddy, we are small delegations, we are terribly busy with so many things, so many issues, documents and meetings and so on. We don't have the time or the staff to do research. So you study the situation, you propose to us what we should do, and we'll say yes or no." So our relationship developed into tremendous confidence. Most of the resolutions were written by me. Reports were written by me. Even speeches were written by me for many years. But I can't claim too much credit because nothing would have happened unless the chairman and other members took the responsibility and made the necessary decisions. And I told them, " Look, I'm a very junior official in the U.N., so there is a limit to what I can do. I will get into trouble if it gets known that I did this or that. You have to take the responsibility for everything." That they very loyally did. And of course they obtained credit for all that I quietly and often secretly helped them in doing. So with their protection I was able, for instance, to discuss with the liberation movements about their needs and the possibilities in the United Nations, contact anti-apartheid groups and seek their advice and help, and propose initiatives for the Special Committee. I was very lucky that I had a job doing something I believed in; it has given me a lot of satisfaction. In the course of my work, I was able not only to help the liberation movements, but to develop closest cooperation with anti-apartheid groups because their activities in promoting public opinion and public action against apartheid were crucial for the effectiveness of the United Nations. It could have been an extremely frustrating job because whatever we did, repression was getting worse in South Africa year after year and people were suffering. But I was not frustrated. Once a proposal I suggested did not get enough support and I was depressed. Robert Resha, a leader of the African National Congress, was with me. He said, " E. S., why are you frustrated? We are not frustrated. It's none of your business to be frustrated. We are going to win." So I kept that in mind. We were able to win small victories and help people. For instance, we set up a fund for scholarships, we set up a fund to help the political prisoners and their families. And they developed into big things. Thousands of South Africans got scholarships. The fund for the prisoners was my idea. And millions of dollars started coming in after a while. Every day we could see that this fund was helping a prisoner or his family, financing defense in a trial and so on. We could derive some satisfaction from what we could do. So we had faith that we were going to win, and that faith never left me. |

This page is part of the No Easy Victories website.