No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000

Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr.

Published by Africa World Press.

home

|

No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000 |

Edited by William Minter, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr. Published by Africa World Press. |

|

An Unfinished Journey by William Minter The 1950s: Africa Solidarity Rising by Lisa Brock The 1960s: Making Connections by Mimi Edmunds

The 1970s: Expanding Networks by Joseph F. Jordan

The 1980s: The Anti-Apartheid Convergence by David Goodman

|

Featured TextThe following text is excerpted from No Easy Victories for web presentation on allAfrica.com and noeasyvictories.org. This text may be freely reproduced if credit is given to No Easy Victories. Please mention that the book is available from http://noeasyvictories.org and http://africaworldpressbooks.com. Robert S. Browne A Voice of IntegrityCharles Cobb Jr.

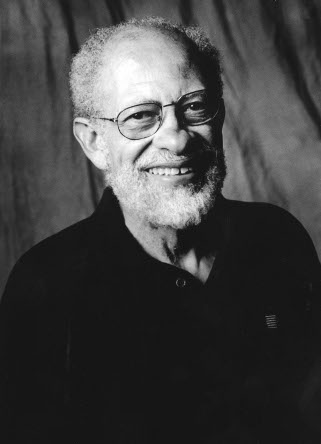

Robert Browne. Photo courtesy of the 21st Century Foundation. Robert S. Browne, who died in 2004 at the age of 79, was a leading thinker and activist best known for his work on black economic development in the United States and for his early leadership in opposing the Vietnam War. He also had a lifelong commitment to Africa and was one of the original founders of the American Committee on Africa. To the end of his life he served as a mentor to other activists. People of many political persuasions trusted him for his personal and intellectual integrity and his respect for all those with whom he worked. Charlie Cobb recalls Bob Browne’s remarkable life, drawing on Browne’s writings and on a 2003 interview by William Minter. With training in economics from the University of Chicago and the London School of Economics, Bob Browne founded three organizations that served as critical, radical voices around economic issues. The Black Economic Research Center founded in 1969 sought to pull in other black economists for black economic development projects, and it published the Review of Black Political Economy. The Emergency Land Fund founded in 1971 fought to protect black land ownership and reverse its decline, especially in the rural South. Also in 1971 he founded the Twenty-First Century Foundation to “promote strategic black philanthropy.” He helped organize the 1967 National Conference on Black Power and presented proposals at the 1972 National Black Political Convention for black economic empowerment. Respected by both radicals and moderates, Browne explored the issue of how demands for reparations to African Americans could be channeled into workable programs for economic development. Browne worked for the U.S. aid agency in Cambodia from 1955 to 1958, and in Vietnam from 1958 to 1961. On his return to the United States, he was one of the earliest active opponents of the war in Vietnam. As he explained in an article in Freedomways in 1965, his marriage to his Vietnamese wife, whom he met in Cambodia, gave him an insight shared by few other Americans at the time. “The fact that I was a non-white, Vietnamese- speaking member of a Vietnamese family frequently made me privy to conversations intended only for Vietnamese ears, and provided me an unusual measure of insights . . . which led me to become a constant and vigorous critic of the United States policy” (Browne 1965, 152–53). His introduction to Africa, interrupted by the time in Southeast Asia, came first in Chicago and then in New York. In a tribute to Paul Robeson published by Freedomways in 1978, Browne wrote:

Browne spent the year 1952 traveling in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, after a short course at the London School of Economics. The trip “internationalized” him, he said in a 2003 interview, and he returned not to Chicago but to New York. He became one of the founders of the American Committee on Africa and a regular participant in the group of volunteers helping out with mailings and other work in the years before he moved to Cambodia. On his return, he joined the board of directors of the organization and continued to be a part of its activities even when his own work took him away from African issues or away from the New York area. Browne worked both inside and outside of the political and economic establishment. In 1980 the U.S. Treasury Department appointed him as the first U.S. executive director of the African Development Bank in Côte d’Ivoire. Debt and the economic conditions in developing nations, especially African nations, figured prominently among his concerns. With Robert Cummings of Howard University, he wrote an early critique of World Bank policies in Africa (Browne and Cummings 1984). He was Jesse Jackson’s adviser on economic policy during his 1984 presidential campaign and from 1986 to 1991 he was staff director of the Subcommittee on International Development, Finance, Trade and Monetary Policy of the House Banking Committee. “The global trading system handicaps Africa,” wrote Browne in a 1995 paper criticizing export restrictions, import duties, and agricultural subsidies to U.S. and European farmers. “While African countries may open their economies more widely to imports and investments from other countries, they may not have the capacity to take advantage of new opportunities for exports in sectors other than primary commodities. “Unfortunately, the architects of the global trading system, including the United States, display very little sensitivity to these issues,” he continued. Nevertheless, “it is in the long-run interest of all peoples [to close] the yawning gap between economic conditions in Africa and in the United States.” |

This page is part of the No Easy Victories website.