No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000

Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr.

Published by Africa World Press.

home

|

No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000 |

Edited by William Minter, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr. Published by Africa World Press. |

|

An Unfinished Journey by William Minter The 1950s: Africa Solidarity Rising by Lisa Brock The 1960s: Making Connections by Mimi Edmunds

The 1970s: Expanding Networks by Joseph F. Jordan

The 1980s: The Anti-Apartheid Convergence by David Goodman

|

Featured TextThe following text is excerpted from No Easy Victories for web presentation on allAfrica.com and noeasyvictories.org. This text may be freely reproduced if credit is given to No Easy Victories. Please mention that the book is available from http://noeasyvictories.org and http://africaworldpressbooks.com. Sylvia Hill: From the Sixth Pan-African Congress to the Free South Africa Movement

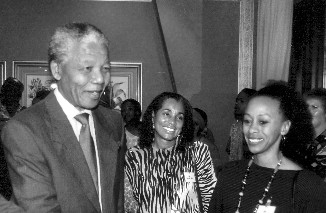

Sylvia Hill, center, and Gay McDougall were among African American activists invited by Nelson

Mandela to visit South Africa in October 1991 on what was called a " Democracy Now" tour.

Sylvia Hill and her fellow local activists in the Southern Africa Support Project were at the heart of the Free South Africa Movement that brought demonstrators to be arrested at the South African embassy. Hill was also one of the key organizers for the Sixth Pan- African Congress in Dar es Salaam in 1974, and for Nelson Mandela's tour of the United States following his release from prison in 1990. Today Hill is professor of criminal justice at the University of the District of Columbia. She serves on the board of TransAfrica Forum. This profile draws on interviews with Sylvia Hill by William Minter in 2003 and 2004. William MinterAt the Sixth Pan-African Congress in Dar es Salaam in June 1974, Sylvia Hill didn't have much time to follow the speeches and debates about race and class, the African diaspora, and the current status of the liberation movements. As one of the key U.S. organizers of the event, she had to focus instead on a host of logistical questions, from finding typewriters to transcribe the sessions to negotiating with translators demanding to be paid in U.S. dollars. " Six PAC," the sixth in the series of Pan-African congresses initiated by W. E. B. Du Bois, came more than two decades after the historic Fifth Congress in Manchester, England in 1945. It was the first to be held in Africa. Hill is aware that many observers discount the congress because of the heated disagreements that were aired, particularly among delegates from the United States and the Caribbean. But there were positive outcomes, she insists. " I've read and I've heard people say that the conference didn't produce anything, and I'm like, wait, wait, wait," she said in a 2003 interview. " It was really Six PAC that led me to return and work on Southern Africa. There were a group of us who committed ourselves that we were going to work against colonialism, and it was based on the investment in this congress and the agenda of the national liberation struggle." Hill and many of the other organizers wanted to establish direct connections between African liberation movements and African Americans. Tanzania, which hosted the event and had fostered wide participation from the United States through its embassy in Washington, was the key venue for bringing people together. Tanzania's President Nyerere was keenly aware of the importance of people-to-people contact and of the critical contribution made by those who work behind the scenes. When national delegations to the congress were scheduled to meet with Nyerere, the all-male group of leaders of the U.S. delegation chose themselves as the five to go, despite a suggestion from veteran activist Mary Jane Patterson that Hill should be included. That night, Hill recalls,

Ambassador Bomani [the Tanzanian ambassador to the United States] came and said to me, " There will be a car to pick you up to take you to the president. You will meet with the president alone, and when the gentlemen get there, you will already be there." I was there half an hour before they got there. I was already on my second cup of tea when they walked in and they were so stunned to see me sitting there. On returning to Washington, Hill and a small group of fellow activists - almost all women - founded a small group called the Southern Africa News Collective, which grew into the Southern Africa Support Project in 1978. They were clear in defining their top priority as the local community. While they recognized the complementary role of national organizations focused on Africa and developed particularly close ties with TransAfrica, they argued that developing a local base of support for African liberation was essential. They raised assistance for Zimbabwean refugees in Mozambique and for the ANC exile school in Tanzania through annual " Southern Africa" weeks with radiothons, public meetings, and speaking engagements in churches and schools. It was this systematic work, Hill says, that built " a kind of social infrastructure of ties to institutions and sectors in the city" and that would later pay off in the Free South Africa Movement demonstrations. The relationship between local groups and other groups working on different aspects of solidarity was dialectical, Hill stresses. If it had all been one large bureaucracy, " we could have never done what was ultimately accomplished." It was local organizing in combination with national media attention to South Africa - and particularly TransAfrica's presence in the national media - that enabled the Free South Africa Movement coalition to sustain daily demonstrations at the South African embassy for a year, in 1984û85. Around the country, coalitions of local activists came together and took their own initiatives, inspired by the growing publicity and informed by resources from national groups. " People have a range of ways they express support. It's everything from sitting in front of the TV and saying, 'right on,' to physically being there. Now if you want them there, you've got to work to get them there," Hill reflects.

What is significant, from the organizer's point of view, is that the person expresses public opposition instead of private disdain for policies. The challenge for the organizer is to find that creative space that will permit ordinary citizens to express collective opposition. It is the task of the organizer to create venues for internal feelings to be expressed publicly. This the Free South Africa Movement accomplished. And therefore, one of our profound lessons of this movement is that one should never underestimate the power of symbolic protests to create a climate for political change. |

This page is part of the No Easy Victories website.