Featured Text

The following text is excerpted from No Easy Victories for web presentation on

noeasyvictories.org. This text may be freely

reproduced if credit is given to No Easy Victories. Please mention that the book is

available for order on-line at

http://noeasyvictories.org and

http://africaworldpressbooks.com.

Chapter 5, The 1980s: The Anti-Apartheid Convergence,

Massachusetts and Beyond

by David Goodman

From pages 151-153. Chapter continues on pages 154-166.

| pdf of complete Chapter 5 (2.1 M)

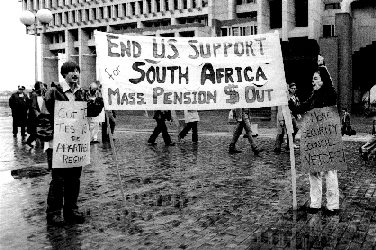

Photo: Demonstrators at Boston's City Hall Plaza demand that Massachusetts pension fund monies

be divested from companies doing business in South Africa. September 16, 1981. Photo @ Ellen Shub.

It was the fall of 1978, and South Africa was about the farthest thing from my mind. I was just

entering college and knew little of this distant, tortured land. A chance encounter with an anti-

apartheid activist changed all that. On a sunny September afternoon during freshman week at

Harvard, I was walking up the steps of the Fogg Art Museum to participate, along with a thousand

or so of my new classmates, in the quaint ritual of having tea with the college president, Derek

Bok. As I approached the front door, a graduate student named Joe Schwartz pressed a leaflet into

my hand.

"Why don't you ask President Bok why Harvard supports apartheid?" he challenged me. He explained

that Harvard had millions of dollars invested in companies doing business in South Africa. I

figured there must be some explanation for this, but I was sufficiently cheeky to venture inside

and go directly over to the university president. He was cradling a teacup, surrounded by a clutch

of awestruck freshman. Was it true, I asked Bok, that Harvard was profiting from apartheid? The

students fell silent. Bok pursed into a tight smile. He replied coolly, speaking of the importance

of remaining "engaged," maintaining "dialogue," and bringing pressure on South Africa from the

inside.

I was unimpressed, and frankly disgusted by his explanation. Two years after the police attack on

protesting students in Soweto, the white regime that I read about appeared to be utterly unmoved

by polite pressure and the occasional diplomatic scolding. The simple reality was that the college

president could not bring himself to part with such profitable investments. My anti-apartheid

activism began that day.

Although I didn't know it at the time, my chance encounter was being repeated on sidewalks, in

living rooms, and in workplaces all across the United States. Schoolteachers, longshoremen,

investment managers, legislators, and retirees were learning of the ways that they were

unwittingly supporting a racist state on the southern tip of Africa. And they were figuring out

that they had the power, right in their own communities, to make a difference.

These realizations did not come about by chance. The explosion of activism in the 1980s in support

of Southern African liberation was the culmination of decades of efforts, reflecting lessons

learned from countless past successes and failures. The singular achievement of U.S. activism in

the 1980s was the transformation of disparate African solidarity movements into a focused,

multiheaded, and surprisingly successful anti-apartheid movement.

My own engagement reflected how the movement had spun off numerous local-- even neighborhood--

initiatives. As a college activist, I joined efforts to force Harvard to divest itself of the

approximately $1 billion that it held in companies doing business with South Africa. I worked with

Harvard's Southern Africa Solidarity Committee, helping organize demonstrations, teachins,

debates, and fasts, and constructing a South African--style shantytown in Harvard Yard.

In 1983 I was involved in launching the Endowment for Divestiture, an alternative donation channel

for Harvard alumni who wanted to pressure the university by contributing to an escrow fund that

would only be turned over to Harvard after it divested from South Africa. Following college, I was

active in several Boston-based anti-apartheid groups, and I participated in demonstrations aimed

at stopping the sale of Krugerrands. I was mostly just a foot soldier in these efforts, one of

thousands around the country engaged in the seemingly quixotic challenge of smashing the pillars

that supported apartheid.

My involvement in the divestment movement led me to want to see for myself what the apartheid of

my protest chants was about. Themba Vilakazi, a friend who was a longtime member of the African

National Congress, told me, "You should go to South Africa if you can get in. But," he added,

"when you come back, you will have a responsibility to tell people about it." In 1984, as a

budding freelance journalist, I journeyed to Zimbabwe and South Africa. I chronicled what I found

there for a variety of U.S. and British publications and ultimately wrote a book about that and

subsequent visits, Fault Lines: Journeys into the New South Africa (Goodman 2002).

In this chapter, I tell the story of U.S. activism in the 1980s by focusing on representative

examples of antiapartheid activism in three key arenas: local, national, and international. At

the local level, I take as a case study the organizing that happened in Massachusetts, which led

to passage of the nation's first statewide divestment initiative in 1983. Former Massachusetts

state representative Mel King and Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Willard Johnson

were at the center of these struggles. The national picture is represented here by Jennifer Davis

and Dumisani Kumalo, both of the American Committee on Africa, and by the work of the Free South

Africa Movement launched in Washington, DC by Randall Robinson. Finally, Ted Lockwood, who spent

the 1970s as director of the Washington Office on Africa and the early 1980s as the international

affairs representative for the American Friends Service Committee, fills in the international

dimension of the solidarity effort.

Global Outrage, Local Actions

South Africa may be an ocean away, but when I arrived to start college in Cambridge in 1978 it was

a hotly debated local issue. Massachusetts, I quickly learned, was a key outpost of the U.S. anti-

apartheid movement. The first university divestment and the first full divestment of a state

pension plan took place there in the late 1970s and 1980s. Chapter 4 on the 1970s recounts the

story of the Polaroid Corporation in Cambridge and how workers there made South Africa a local

issue. It also relates the early organizing done by Randall Robinson while he was a Harvard Law

School student and before he became executive director of the African American lobby TransAfrica.

In the late 1970s, students in Massachusetts took up the cause of South African divestment. The

first school in the country to divest was Hampshire College in western Massachusetts in 1977. The

Southern Africa Solidarity Committee at Harvard, of which I was a member, formed during this

period. It brought members of African liberation groups to campus, held material aid drives for

Zimbabwe, and sponsored concerts by Abdullah Ibrahim (Dollar Brand) and Bob Marley. Around the

city, the Boston Coalition for the Liberation of Southern Africa (BCLSA) played a key role in

building a larger divestment initiative. A key member of BCLSA was Themba Vilakazi, Boston

representative of the ANC. In 1985 Vilakazi formed the Fund for a Free South Africa (FREESA),

which became the de facto leader of anti-apartheid work in the Boston area.

Two African American leaders played central roles in anti-apartheid efforts in Massachusetts. Mel

King is a lifelong community activist in Boston. He headed up the Boston chapter of the Urban

League in the late 1960s--described by a fellow activist as "the first Black Power Urban League

chapter in the country"--until his election as a Massachusetts state representative in 1972.

Willard Johnson was a professor of political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

for over 30 years, until his retirement in 1996. The founder and head of the Boston chapter of

TransAfrica and a member of the group's national board, he was a guiding force in numerous African

solidarity efforts around Boston from the late 1960s onward, and he spearheaded Boston's Free

South Africa Movement in the 1980s.

Massachusetts was among the first states to put issues of African liberation before state and local

political bodies. In 1973û74, for example, state representative Mel King introduced a bill in the

Massachusetts legislature aimed at preventing the port of Boston from handling Rhodesian chrome.

This strategy was conceived during a visit to Boston by ANC president Oliver Tambo in late 1969 or

early 1970. Tambo met activists at the home of Willard Johnson in suburban Newton. Among those in

attendance was Mel King. Johnson recalls, "What Tambo was essentially pointing out was that there

are ways to use legislative and governmental machinery at the local level on these foreign policy

issues."

Mel King's focus on South Africa was a natural outgrowth of his racial justice work in Boston. He

explains, "One's involvement in [anti-apartheid work] is based on one's understanding of the racial

nature of this society. And so a situation like South Africa is just an extension of here. So if

you're working on it here, you see the relevance of working on it anywhere it exists."

Continued on pages 154-166, Order book.

|