No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000

Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr.

Published by Africa World Press.

home

|

No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000 |

Edited by William Minter, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr. Published by Africa World Press. |

|

An Unfinished Journey by William Minter The 1950s: Africa Solidarity Rising by Lisa Brock The 1960s: Making Connections by Mimi Edmunds

The 1970s: Expanding Networks by Joseph F. Jordan

The 1980s: The Anti-Apartheid Convergence by David Goodman

|

Featured TextThe following text is excerpted from No Easy Victories for web presentation on allAfrica.com and noeasyvictories.org. This text may be freely reproduced if credit is given to No Easy Victories. Please mention that the book is available from http://noeasyvictories.org and http://africaworldpressbooks.com. Walter Bgoya: From Tanzania to Kansas and Back Again

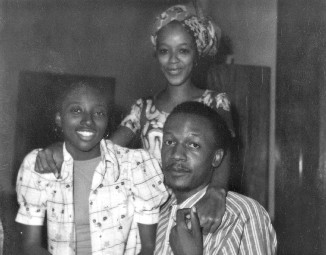

From left: Kathy Flewellen, Geri Augusto, and Walter Bgoya, in Dar es Salaam, 1974. Flewellen

and Augusto were among the organizers of the Sixth Pan-African Congress. Bgoya was then director of the

Tanzania Publishing House. Walter Bgoya is the managing director of Mkuki na Nyota, an independent scholarly publishing company in Dar es Salaam, and chairman of the international African Books Collective. From 1972 to 1990 he directed the Tanzania Publishing House, which played a major role in making Dar es Salaam a center for progressive intellectuals from around the world. Its publications included Walter Rodney's How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Agostinho Neto's Sacred Hope, Samora Machel's Establishing People's Power to Serve the Masses, and Issa Shivji's Class Struggle in Tanzania. In this essay, written for No Easy Victories, Bgoya reflects on his experiences and work in the 1960s.

Walter BgoyaAt the end of July 1961, I and several hundred other African students left our different countries on scholarships offered by the African American Institute. I was placed at the University of Kansas. Before going to the university I stayed for a month with a generous and deeply religious white family in a little town called El Dorado. The stay with this family offered me the first experience of living in the United States. I was taken to church every Sunday and stood in line with the priest after service to shake hands with the whole congregation, as the African student who was staying with the Cloyes. Not having seen any black person in the church, I was intrigued and asked my hosts if there were any black people in the town. Yes, I was told, there were Negroes (the term in use then), but they had their own churches. I thought it strange that there were separate churches for black and white people, but I did not want to embarrass my family any further so I did not pursue it. I did, however, ask if I could meet a family of black people and arrangements were made. The visit did not go well, unfortunately, perhaps because neither they nor I were prepared for it. Only one member of the family greeted and sat with me - quite uncomfortably, it was obvious. The others went on with their business, oblivious to my presence, not even greeting me, which as an African I found insulting. Perhaps the fact that I had been brought there by a white family made me part of the white world with which they had problems. I was deeply disappointed. I learned later that relations between Africans and African Americans were complicated and that it would take special efforts to make friends with people of my own race. Going to the university in September was the beginning of four years of intense involvement in the struggle against different forms of racial discrimination at the university and in the town surrounding it, leading to the 1964 takeover of the administration building. Protesters were arrested, tried, and acquitted. The story has been told in This Is America? The Sixties in Lawrence, Kansas, by Rusty Monhollon (2002). The struggle at the university exposed me to unpleasant experiences with rightist groups, including the John Birch Society and the Ku Klux Klan, who burned a cross outside my apartment. I was called all sorts of names in threatening letters and phone calls - I was a " communist" and a " foreign agitator" - and I was advised to take these threats seriously. But while my involvement in a leadership position in the campus civil rights movement was deeply resented by right-wing white people, we had great support from liberal and progressive white students and faculty members. I returned to Tanzania in 1965, having learned many lessons from my years in the United States. I had immersed myself in the struggle for rights and human dignity regardless of my status as a foreign student. I rejected the notion that as a foreigner I had no business getting involved in black people's struggles; after all, I was not spared the indignities of racial discrimination in housing or refusal of service in restaurants and other places. I learned to speak up and to challenge authority when I believed it was wrong. Back home, my outspokenness did not endear me to my superiors at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where I was assigned to work, or to politicians who did not accept that their ideas could be challenged. A oneparty state under the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), Tanzania was hierarchical and authoritarian, and one was expected to conform and to do as one was told. It was clear after a short time in the foreign ministry that I needed to make some alliances at the workplace and outside if I was to survive. A group of youth leaders had been invited by Mwalimu Nyerere soon after the 1967 Arusha Declaration (TANU's policy on socialism and self-reliance) to form the TANU Study Group, a kind of think tank for the ruling party. I was asked to join and we met once a week on Sundays to discuss current political and economic issues, both national and international, and to forward recommendations to the party leadership. Major issues during that period were the struggles for liberation from Portuguese colonialism in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau; settler colonialism in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and South West Africa (Namibia); apartheid in South Africa; and issues in other places such as French Somaliland (Djibouti), Comoros, Sahara, and, outside Africa, East Timor. The Vietnam War, the struggle for admission of the People's Republic of China to the United Nations, the Soviet Union's invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, and support for Cuba were among the other issues that exercised us. In the Ministry of Foreign Affairs I was assigned to the Africa desk and it was there that I had the opportunity to meet and work with liberation movements and their leaders. I also worked with the OAU's Liberation Committee, which had its headquarters in Dar es Salaam. Not all Tanzanians supported the government's policy of supporting the liberation movements. There were some high officials and politicians who thought Tanzania was unduly exposing itself to dangers and was expending financial and other resources it could ill afford in support of the wars of national liberation in Africa. They did not say this openly - who would dare question Mwalimu Nyerere? Nevertheless they slowed things down, frustrated the more radical supporters of the liberation movements, and even occasionally resorted to calling them CIA agents as a way to discredit them. Relations between the Tanzanian government and the liberation movements were generally good but difficult situations did sometimes arise, especially where there were two or more liberation organizations from the same country. Cold War politics influenced debates and decisions in international forums inside and outside Africa. There were also contradictions. On one hand, the liberation movements were grateful for the support they enjoyed from Tanzania and from Mwalimu Nyerere; on the other hand, they feared that Tanzania might exert undue influence on their " internal affairs." A good example of this was the response of the liberation movements to the 1969 Lusaka Manifesto. The document, which had been written by Nyerere and adopted by the leaders of the Frontline States, put forward the position that the heads of state would dissuade the liberation movements from continuing the armed struggle if the Portuguese and South African regimes accepted the principles of independence and majority rule and agreed to start the process of negotiations to that end. The liberation movements were incensed by this position. In the first place, they argued, it had been taken without consulting them. Second, the decision on the means by which to pursue the struggle was a sovereign decision that only they and no one else could take. Third, each struggle had its own character and there could not be one position that would fit all. The Lusaka Manifesto was adopted by the OAU. We argued with the liberation movements that armed struggle was not an end but a means toward an end, and if that end could be secured peacefully, there would be no reason for war. But the liberation movements never quite accepted the position. In 1971 I had the honor to be assigned to draft the Mogadishu Declaration, which nullified the Lusaka Manifesto. The declaration argued that since the Portuguese colonialists and the apartheid regime had not responded positively, frustrating the hopes of the OAU, there was no alternative but to continue to support the armed struggle. The 1960s and 1970s were exciting times in Tanzania's history. Because of Mwalimu Nyerere's leadership and his desire to build an African socialist society based on the African concept of ujamaa, he attracted many Western intellectuals. For African Americans, Tanzania came to embody many of their historical aspirations, including the possibility of returning to Africa to stay, which a few of them did. African Americans coming to Tanzania often arrived with names of individuals and institutions to contact, including in some cases the foreign ministry, and I was privileged to be one of the individuals who was contacted. It was a period of mutual discovery between those African Americans and Tanzanians, with unresolved questions and frustrations but also fulfillment, especially in 1974 around the time of the Sixth Pan-African Congress. Some members of the Drum and Spear group - Charlie Cobb, Anne Forrester, Courtland Cox, Geri Stark (Augusto), Jennifer Lawson, Kathy Flewellen, and Sandra Hill - stayed for short periods of time. Others, such as Bob Moses and Professor Neville Parker, stayed longer and made invaluable contributions to Tanzania in the field of education. Bill Sutherland stayed the longest, followed by others such as Monroe Sharp and Edie Wilson. Walter Rodney, who was at the University of Dar es Salaam, had great influence on discussion and debates around the period of the Pan- African Congress. I left the foreign ministry in 1972 to join and manage the Tanzania Publishing House. There, my involvement in liberation support activities actually increased, as I was now less constrained by diplomatic and civil service orders. Publishing became another front in the struggle. Looking back after the end of apartheid and the liberation of the continent, we salute those who bore the brunt of the enemies' blows, and we remember with respect and pride those who paid the supreme price. Among those who worked together, friendships and comradeship endure, along with a feeling of connection to a larger network. On all continents there are still many who remain committed to freedom and to inevitable victory of the next stage of the African revolution. As before, victory will not be not easy, but it is essential. |

This page is part of the No Easy Victories website.