Featured Text

The following text is excerpted from No Easy Victories for web presentation on allAfrica.com and noeasyvictories.org. This text may be freely

reproduced if credit is given to No Easy Victories. Please mention that the book is available

from http://noeasyvictories.org and

http://africaworldpressbooks.com.

Peter and Cora Weiss:

"The Atmosphere of African Liberation"

by Gail Hovey

This profile highlights two activists who have played significant roles in

the Africa solidarity movement and other progressive causes for over 50

years. Emphasizing their involvement in Africa issues, particularly in the

1950s and 1960s, it draws in part on interviews with Cora Weiss by William

Minter in 2003 and by Gail Hovey in 2005, and on an interview with Peter

Weiss by William Minter in 2003.

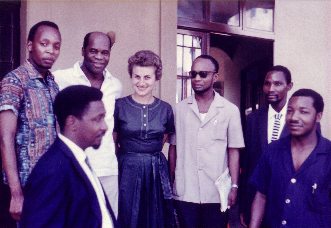

Right: Cora Weiss in Dar es Salaam, probably in 1965.

Back row, from left: Pascoal Mocumbi, Eduardo Mondlane,

Weiss, Amilcar Cabral. Others in the photo are not

identified. Photo courtesy of Cora Weiss.

For most of those who know Peter and Cora Weiss, personally or by

reputation, Africa is not the first connection that comes to mind.

Since the 1960s, Cora Weiss has been prominent in the peace movement.

She was an early member and one of the national leaders of

Women Strike for Peace, which played an important role in bringing an

end to nuclear testing in the atmosphere. Cora also served as co-chair of

the massive November 15, 1969 mobilization in Washington, DC to end

the war in Vietnam, and she was one of the leaders of the June 12, 1982

antinuclear demonstration that drew an estimated 1 million people to New

York City. She has been president of the international Hague Appeal for

Peace since its founding in 1996. Lawyer Peter Weiss has taken the lead in

national and international groups of lawyers opposing nuclear weapons and

in the Center for Constitutional Rights, which has pioneered human rights

law on both domestic and international fronts since its founding in 1966.

In the 1950s, however, it was Africa and the excitement of the independence

struggles that inspired their engagement in international issues. The

˘atmosphere of African liberation÷ and the personal contacts they made

during the decade, recalled Cora Weiss, set the trajectory for their lifelong

involvement with global issues.

Peter Weiss was 13 when his family, fleeing the Nazi onslaught, left

Vienna for France in 1938. They reached New York in 1941, where he

attended high school before being drafted into the army and later working

with the U.S. military government in occupied Germany. After graduating

from Yale Law School, he directed the International Development Placement

Association, a predecessor of the Peace Corps. That job took him to

West Africa, where he established close contacts with nationalist leaders

such as Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria. This experience consolidated the progressive

internationalist views that he had absorbed at the Foundation for

World Government started in 1948 by Stringfellow Barr, former president

of St. John's College, Peter's alma mater.

Cora Weiss first came into contact with Africa as an undergraduate at

the University of Wisconsin in Madison in the early 1950s. She met law

student Angie Brooks from Liberia, who later became the first woman to

head the U.N. General Assembly. Cora worked with African and Indian

foreign students to organize a speakers' bureau that sent students around

the state to talk about their countries. The speakers earned $10 per speech,

which helped with their school expenses.

In 1957, the newly married couple spent months traveling through

West Africa. It was Peter's second trip and Cora's first. In the 1950s, they

also became actively involved with the work of the American Committee

on Africa in New York. Peter later came to serve as president of the organization,

while Cora took on ambitious projects as a volunteer. She organized

a 1,000-person dinner for President Kwame Nkrumah at the Waldorf-

Astoria in 1958, an event co-sponsored by ACOA with the NAACP and

the Urban League. She also coordinated the Africa Freedom Day rally at

Carnegie Hall in 1959, featuring Tom Mboya of Kenya. From 1959 to 1963

Cora directed the African-American Students Foundation, which brought

almost 800 East African students to study at U.S. colleges and universities.

Over the next decades, Peter and Cora Weiss continued their involvement

with Africa even as their primary attention turned to other issues.

They had been close friends with Eduardo and Janet Mondlane when the

Frelimo leader worked at the United Nations from 1957 to 1961, and they

maintained close ties with the family after Eduardo was assassinated in

1969. They met Oliver Tambo on his first visit to the United States in 1962

and became friends with him and his family. The Samuel Rubin Foundation,

which Cora Weiss directed, was part of a small cluster of progressive

funding organizations and individuals that paid attention to Africa

even when African issues were not in the news. Typical of its progressive

vision was its support for Robert Van Lierop's film A Luta Continua, a

documentary on Frelimo filmed in liberated Mozambique that became an

exceptional educational and organizing resource. The foundation was also

consistently an important source of support for The Africa Fund.

Cora was associated with Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts,

the first U.S. college to begin divesting its holdings in companies

operating in South Africa. In 1977 Adele Simmons, the new president of

the college, asked Cora to become a member of the board of trustees. Simmons's

predecessor, Charles Longsworth, had failed to win student trust,

and the Committee for the Liberation of Southern Africa had occupied the

college administrative offices in May of that year. During the occupation,

Longsworth had finally acted, reluctantly announcing that Hampshire

would sell stocks in the offending corporations. Following her appointment

to the board, Cora became a member of the Committee of Hampshire on

Investment Responsibility, which set guidelines firmly establishing the ban

on South African investment (Dayall 2004; Shary 2004).

Present at the founding of ACOA, Peter Weiss encouraged George

Houser to take the position of executive director in 1955. An active board

member and longtime president of the board, Peter provided important

leadership, fully supporting the need for close working relationships with

the liberation movements. Peter also provided legal expertise on a number of

occasions. In 1967 he assisted two South Africans, attorney Joel Carlson and

recently arrived exile Jennifer Davis, who were working frantically¨and as

it turned out, successfully¨to save the lives of 37 Namibians who had been

charged under South Africa's Terrorism Act. In 1972 Peter was succeeded as

ACOA president by black community leader Judge William Booth, a former

New York City commissioner for human rights. Peter remained active on

the board into the 1990s (Houser 1989). He also served on the board of The

Africa Fund until it merged into Africa Action in 2001.

In a 2003 interview, Peter recalled that his early interest in Africa came

from his involvement with the Foundation for World Government, where

he quickly concluded that a world so divided economically could never

function under a world government. His focus had turned to economic

disparities and the attempt of the new African countries to climb out of

the condition that had been imposed on them by the colonial powers. The

world today, he insisted, confronts the same issue: to address ˘the gulf

between the rich and the poor, both internally and globally.

|