Featured Text

The following text is excerpted from No Easy Victories for web presentation on allAfrica.com and noeasyvictories.org. This text may be freely

reproduced if credit is given to No Easy Victories. Please mention that the book is available

from http://noeasyvictories.org and

http://africaworldpressbooks.com.

Public Investment and South Africa

Julian Bond

At the first national Conference on

Public Investment and South Africa in

1981, some 200 state and municipal

legislators from across the United

States attended workshops on drafting

socially responsible legislation,

among other topics. Held in New York

City on June 12–13, the conference

also drew trade unionists, investment

experts, church leaders, academics, and

grassroots organizers. The conference

sponsors included ACOA, AFSC, the

Connecticut Anti-Apartheid Committee,

Clergy and Laity Concerned,

the Interfaith Center on Corporate

Responsibility, TransAfrica, the United

Methodist Office for the U.N., and the

Washington Office on Africa.

For the opening session at the United

Nations, Ambassador B. Akporode Clark

of Nigeria, then chair of the U.N. Special

Committee Against Apartheid, welcomed

the participants. The keynote

address, excerpted here, was given by

SNCC veteran and Georgia state senator

Julian Bond.

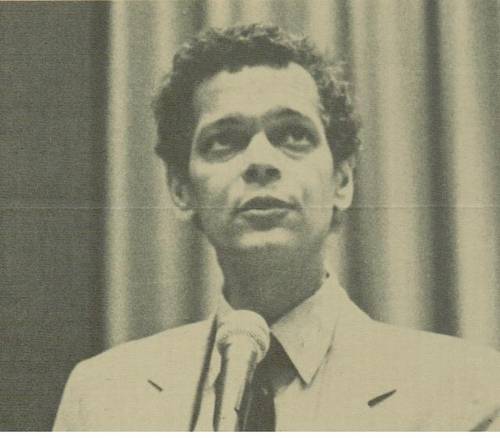

State legislator Julian Bond in 1981. Photo courtesy of Richard Knight.

Thank you a great deal for the kind and warm welcome. I think

most of us who work on African issues, who are scattered throughout

the United States, begin to develop a feeling of isolation and

estrangement. So it is extremely gratifying to discover that we are

many and diverse, that those of us represented here in fact are representatives

of a larger group of people scattered throughout the 50 states of the

U.S. and that our cause is just and our success virtually assured.

Among all of us who are gathered here, there is a particular group:

legislators and council members, who are here as part of the responsibility

of our offices because we are all sworn to uphold the public good. There

certainly could be no greater good than the cause for which we gather, the

advancement of the struggle for the independence of Southern Africa.

We are here to complete the process of halting American complicity

in the most hideous government on the face of the planet, the one system

where racial superiority is constitutionally enshrined. We gather here at

a time when even the most moderate advances away from complicity are

being compromised, abandoned and withdrawn.

In less than six months, the new government of the U.S. reversed even

the halting Africa policies of the Carter administration and has embarked

on a course of arrogant intervention into African affairs in the most hostile

way. From Cape Town to Cairo, the American eagle has begun to bare his

talons. Our secretary of state is a man who pounded his palms on the table

like tom-toms when African affairs were discussed in the Nixon White

House. Our new ambassador to the U.N. sees callers [a high-ranking South

African military intelligence team that came March 15, 1981]. [First] she

says she does not know [them] and then denies seeing them at all. When

her visitors are discovered to have entered the U.S. illegally and their hospitality

revealed to be a violation of policy, she dismisses all complaints as

if the policy had been already revised.

Unfortunately, she was right. America’s policies towards Africa have

changed. They have changed from benign neglect to a kind of malignant

aggression. In Mozambique, starvation is added to the American arsenal.

On the high seas, the American oil companies, Mobil, Exxon, and Texaco

have joined European interests in breaking the OPEC embargo to South

Africa. On Capitol Hill there is the intensity of Soviet competition in

Africa, not humanitarian concerns, which conditions American aid to the

continent. Mineral rights are exchanged for human rights.

In South Africa itself there is no mistaking the increased militancy,

each group adding momentum to the irresistible motion of liberation.

But our concerns are here. Our cause is to take whatever action we can

to end American complicity with this international problem [apartheid].

Our contribution is to pull together those forces—legislators, investment

experts, trade unionists, student activists, that growing constituency for

freedom in South Africa—to facilitate the expansion of public prohibitions

against the expenditure of public funds for inhuman purposes. In

short, we intend to end American investment in evil. The evil, of course, is

the system of apartheid in which four and a half million whites absolutely

dominate 20 million nonwhites, denying them every vestige of humanity.

As the second-largest foreign investor, the U.S. plays a key role in keeping

apartheid afloat. The net effect of American investments, according to

former senator Dick Clark of Iowa, has been to strengthen the economic

and military self-sufficiency of South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Our cause, then, is to end American complicity with this evil. But we

must know the course of the rapidly shifting climate around us. The loudest

voice on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee today belongs to Senator

Jesse Helms, Republican of North Carolina and apologist for South Africa’s

fascists. The new president of the U.S. had already announced even before

his nomination and election his intentions to subsidize subversion in

Angola; he has sent repeated assurances to South Africa’s white population

that the U.S. will tolerate their genocide. He has further delayed the liberation

of Namibia, rewarding South Africa’s intransigence. He has made the

American colossus he professes to adore bow down before a small tribe of

racist tyrants.

We are here, then, to force the disengagement of our commonly held

wealth from this evil. I think we all realize that this will be a difficult and

time-consuming process, for we are in effect opposing the whole of American

history. The current condition of American black people, political

and economic, is more than well known. We gather here to ask the U.S. to

honor the principle that no person’s worth is superior to another, to do in

foreign affairs what is yet to be done at home.

If it is difficult, our task is not impossible. Events in South Africa daily

demonstrate that we are a part of a quickening struggle whose outcome

has never been in serious doubt. We can make a great contribution to that

struggle if all who truly believe in freedom will join us. Ours, then, is a

subtle request; to ask our neighbors, the people with whom we share the

country, to refuse to finance the domination of one set of human beings by

another.

Surely that is a reasonable appeal. South Africa today constitutes a

direct personal threat to us all. Forty years ago, Adolf Hitler demonstrated

that genocide is yet possible even in democracy, even among people who

look alike. It is evil supreme and we cannot allow it to continue; to be

neutral on this issue is to join the other side.

|