No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000

Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr.

Published by Africa World Press.

home

|

No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000 |

Edited by William Minter, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr. Published by Africa World Press. |

|

An Unfinished Journey by William Minter The 1950s: Africa Solidarity Rising by Lisa Brock The 1960s: Making Connections by Mimi Edmunds

The 1970s: Expanding Networks by Joseph F. Jordan

The 1980s: The Anti-Apartheid Convergence by David Goodman

|

Featured TextThe following text is excerpted from No Easy Victories for web presentation on allAfrica.com and noeasyvictories.org. This text may be freely reproduced if credit is given to No Easy Victories. Please mention that the book is available from http://noeasyvictories.org and http://africaworldpressbooks.com. Jennifer Davis: Clarity, Determination, and Coalition Building

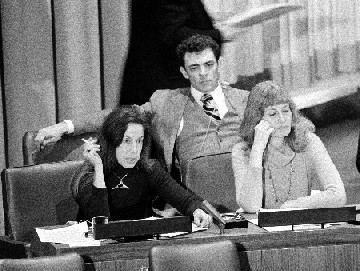

Jennifer Davis, left, testifies at the United Nations on South Africa's apartheid policies,

November 1980. Karen Talbot of the World Peace Council was also among the witnesses from

nongovernmental organizations. Jennifer Davis and George Houser had been colleagues for more than a decade when he retired from the American Committee on Africa in 1981 and she became the organization's second executive director. A South African exile, she knew the organization well from her years as its research director and led it through the critical decades of the 1980s and 1990s. This profile is based in part on interviews with Davis by William Minter in 2004 and 2005. It also draws on interviews with Robert S. Browne by William Minter in 2003, and with Dumisani Kumalo by Gail Hovey in 2005. Gail HoveyUpdate July 11,2020: For a YouTube video of a powerful memorial service for Jennifer Davis, who died in October 2019, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0vAWRAEPI-4 Jennifer Davis never planned to go into exile from South Africa. But by 1966, organizing inside the country had become very difficult. Most major organizations were banned, and an increasing number of the individuals she worked with, at both the grassroots and leadership levels, were in detention or under house arrest. Exile was never simple, she says. Activists had to grapple both with their conscience about " leaving the struggle" and with the authorities, who used the issuing of passports as a means of control. Leaving South Africa happened quite suddenly, in a traumatic few weeks. It started by my husband [lawyer Mike Davis] leaving to visit my brother, traveling on a valid passport. That was followed by several calls from the police indicating that they believed he had left illegally and that I would soon be subjected to some form of house arrest order, as would he if he returned. Mike had done many political cases in South Africa, including several where he was instructed by the Tambo-Mandela law firm. In New York, Mike Davis made contact with people connected to the American Committee on Africa, and over time they helped him reestablish his legal career. Jennifer Davis arrived with their two small children and began her adjustment to life in the United States. An early experience stands out in her mind as particularly instructive. She was invited to dinner by friends of her parents who lived on Manhattan's East Side.

They had an absolutely beautiful house with lots of original artwork, an El Greco in their dining room. One of the guests said to me - I think we were already sitting down after dinner -you must see great differences between South Africa and here. And I said, well, there are some differences, but there's not such a lot of difference. I see a tremendous number of very poor black people, and a lot of very rich white people. And she pulled herself up to her rather portly height and said, there are no poor people in America. Davis had been speaking her mind since high school, when she dared to argue with her Afrikaans teacher about the 1948 elections. The daughter of a South African father and a German mother who left Germany in the early 1930s, she came to understand the meaning of the Holocaust from her parents and maternal grandmother. For Davis, " never again" meant that every Jew should be an activist, resisting religious and racial oppression wherever it occurred. A member of the Unity Movement in South Africa, Davis describes herself as a very serious young woman.

In the United States Davis found a place at ACOA, where she became the research director. She established extensive files that were a resource for activists and journalists and provided the information for ACOA's and The Africa Fund's numerous presentations before U.N. and U.S. government committees. During the burgeoning divestment campaign, items like " Fact Sheet on South Africa" and " Questions and Answers on Divestment" were used in virtually every state and local campaign. Davis's home became a temporary landing place for countless people - Africans, Europeans, and North Americans - who had been recently expelled from their countries of origin or were in New York temporarily to carry out a U.N. assignment or use ACOA's resources. One such guest was activist poet Dennis Brutus. In 1966 Brutus had just been released from the Robben Island prison in South Africa and went on tour in the United States for ACOA. Davis remembers that he used to wander around her apartment in the middle of the night, muttering poetry; her kids were fascinated by him. He later settled in the United States and spearheaded work on the international sports boycott. Over more than three decades, Davis continued to host delegations and individuals from liberation, protest, human rights, and trade union movements throughout Southern Africa, providing the opportunity for them to inform and update activist Americans on the progress of their work. In 1981, on the retirement of George Houser, Jennifer Davis took over the leadership of the American Committee on Africa and The Africa Fund, a position she would hold until her retirement in 2000. At the time, ACOA's board was chaired by William Booth, a black lawyer and district court judge who was a former New York City commissioner. Announcing Davis's appointment in ACOA Action News (spring 1981), Booth said, " She has gained a reputation as an authority with few peers in analyzing political and economic developments in Southern Africa. . . . She brings the same commitment and integrity that are characteristic of George Houser. What was so well begun will be well continued under her leadership." It was not quite that simple. This was, after all, the American Committee on Africa, and according to board member Bob Browne, some people thought it was crazy to appoint a South African to head it. And not only a South African, but a white Jew. Browne went on to say that it did not remain a problem because Davis quickly won over any skeptics. But that is also an oversimplification. While serving as director, Davis traveled around the country speaking in a wide variety of venues. She had to deal with sensitive questions regarding her credibility. Although he says they didn't talk about it at the time, Dumisani Kumalo, ACOA's project director and a fellow South African, was well aware of the challenges she faced. " We were involved in a political struggle and she was a white Jewish woman in this struggle against racism. So she was up against it in the U.S., with its racism." Davis recalls her debates on U.S. television with South African homeland leader Gatsha Buthelezi, who worked with the South African government to lobby against sanctions. " He attacked me as the 'white lady.' He's black; I'm white. What do I know? He was arguing that we should have more investment." Davis learned the value of speaking, whenever she could, in joint appearances with a black colleague. " I developed, I think, a fair amount of credibility, but to have David Ndaba from the ANC or Dumisani Kumalo meant that me being a 'white lady' didn't matter." Davis remained a strong advocate for strengthening sanctions and keeping them in place until there was a genuine transfer of power in South Africa. In 1989 Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Herman Cohen admitted, " Sanctions have had a substantial impact on persuading white South Africans of the need for a negotiated settlement" (Wall Street Journal, June 30, 1989). Then he argued that now was the time to lift sanctions, to reward the changes that had been made. Davis was quick to reply. " What has changed," she said, " is the white power structure's sense of permanence and invulnerability . . . The economy is badly shaken - o growth, unemployment for whites, inflation" (1989). She called for the imposition of comprehensive sanctions. From the beginning of her involvement with ACOA, one of Jennifer Davis's key contributions was to insist on an anti-imperialist focus for the American anti-apartheid work and for the work in support of liberation movements in the rest of Southern Africa. While affirming the importance of human rights and political prisoner campaigns, Davis insisted that ACOA concentrate on exposing and weakening the support that American institutions were giving to the white minority regimes. Beginning in the 1970s, Davis began making trips to Africa. In August 1974 she traveled to Tanzania to spend time with Frelimo, visiting, among other places, the Mozambican movement's hospital in Mtwara.

We were supporting, through the Rubin Foundation, the hospital in Mtwara. It wasn't a hospital, it was a small house, and they'd bring people across the border from Cabo Delgado. The staff greeted me as I came up to the building, and then they held me in the door, and they said to the respective people in the beds, this visitor is coming from the United States and she would like to come and talk with you, and is it all right? And everybody said yes, and then I went inside. I went to a hospital in Zambia where the doctors took me around and nobody ever told the patients what was happening. Davis was enormously impressed by Frelimo. She understood them to be seriously attempting to engage the people not as victims but as participants. When Mozambique's president Samora Machel and 33 others died in a plane crash on October 19, 1986, Davis flew to Maputo to attend the funerals. ACOA's relationships with Frelimo were too enduring not to express solidarity in person. She recalls: Perhaps the most memorable minutes of my stay in Mozambique were 15 minutes spent with Grata Machel an hour before leaving. She had borne herself with great dignity throughout the public ceremonies. Now, face to face, she embraced me, listened to my messages of sympathy and solidarity and said, " We have always known that we had many friends, but it is good that you are here, so we can touch." Then she went on to talk about tasks ahead. (Davis 1986) In January 1990, just before the elections that would bring SWAPO to power in Namibia, Davis traveled to Windhoek. She wanted, she says, to reconnect with individuals and groups throughout the country, to understand what might happen in the next few weeks and the ways that solidarity could continue after the elections. She went north to Oshikati, where SWAPO had strong support. She talked to a wide range of people, from Toivo ya Toivo and other SWAPO leaders to women's groups and Lutheran church activists. Finally, in 1994, Davis returned to South Africa to serve as an official observer for the South African election. She had traveled a long distance in the three decades she had been away. A Jewish secular intellectual, she had come to lead organizations whose constituencies were most often Christian, or black, or both. That the churches were major players in the anti-apartheid movement in the U.S. was something that she had to get used to. She came to win the respect of those with whom she worked. At a party held in her honor in 2003, one of the speakers was Harlem minister Canon Fred Williams, a board member of ACOA and co-founder with Wyatt Tee Walker of ACOA's Religious Action Network. The network was open to all religious traditions but was made up predominantly of black churches. They had answered a call from religious leaders in South Africa to protest detentions, work for sanctions and send prayers and messages of solidarity. " Here was this Jewish woman," Williams said, " and she is the one who made it possible for the Religious Action Network to do its work, this coalition of primarily black, male clergy and their churches. The public Jennifer, cold to some, aloof, hard to connect to, yes, but so reliable as the one to look more deeply, to insist on principle, to keep focused even in the face of terrible opposition" (2003). |

This page is part of the No Easy Victories website.