No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000

Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr.

Published by Africa World Press.

home

|

No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000 |

Edited by William Minter, Gail Hovey, and Charles Cobb Jr. Published by Africa World Press. |

|

An Unfinished Journey by William Minter The 1950s: Africa Solidarity Rising by Lisa Brock The 1960s: Making Connections by Mimi Edmunds

The 1970s: Expanding Networks by Joseph F. Jordan

The 1980s: The Anti-Apartheid Convergence by David Goodman

|

Featured TextThe following text is excerpted from No Easy Victories for web presentation on allAfrica.com and noeasyvictories.org. This text may be freely reproduced if credit is given to No Easy Victories. Please mention that the book is available from http://noeasyvictories.org and http://africaworldpressbooks.com. From Local to National: Bay Area Connections

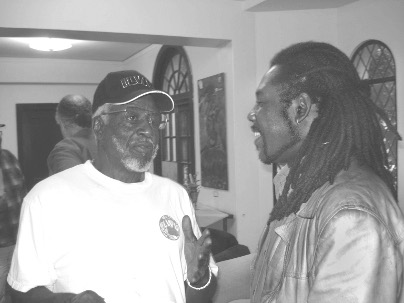

Leo Robinson

U.S. trade unionist Leo Robinson and South African student Steve Nakana greet each other at an African Diaspora Dialogue meeting in Berkeley, California, 2006. Nakana told the gathering that when he was a student at the ANC school in exile in Tanzania, he had received packages from people in America, with clothing, books, and other items. Robinson told of packages that he and other union officials had put together to send, adding with a laugh that they had often slipped chewing gum, candy, or dollar bills into the pockets of clothes just before sealing them. Nakana, smiling broadly, stood up and said he was one of those who opened such packages. “It felt like Christmas,” he added. Photo courtesy of Nunu Kidane. In the San Francisco Bay Area, as elsewhere in the country, the antiapartheid campaign of the 1980s and 1990s was closely tied to the local contours of progressive politics (see Walter Turner’s chapter on the 1990s). At the same time, its impact was projected into the national arena through multiple organizational links and networks. As early as 1979, Berkeley, California, became the first U.S. city to opt for divestment through a public ballot initiative spearheaded by Mayor Gus Newport. In the 1980s Newport challenged the membership of the U.S. Conference of Mayors to follow Berkeley’s example. Another influential Bay Area figure with national connections was labor activist Leo Robinson, of Local 10 of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union. Robinson recalled the growth of the local’s activism in an interview with Walter Turner in 2005. Around 1974 or 1975 I happened to meet the girlfriend of my working partner. He was going to San Francisco State, and he brought her by the house one day. And right away I could tell she had an African accent. And she said that she was from South Africa and I said oh. And I said when you get back home, you’re going to be in pretty good shape, huh? And she said I can’t go back. And I said what do you mean, you can’t go back? She said if I go back after I’ve finished my schooling, I’ll be arrested the minute I step off the plane. And that was my first introduction to apartheid. I had not yet made a genuine connection. I started to know about it because when you picked up a copy of Jet from time to time you would see something in there about what was going on in Africa. And it’s in the back of your head, right? And then in 1976 when the student uprising occurred in Soweto, the massacre of innocent, unarmed people—it’s a gut reaction that you act from then. But as you get to be knowledgeable about what it is that you’re looking at, then it’s a whole different focus. Because the gut reaction does not last long. [A massacre is] in the news one day and then it slowly dies out and it’s forgotten about by people. Until you actually start delving into things, you never know what’s occurred prior to when you came along. William Bill Chester, who was a member of Local 10, who then moved to the International as a regional director for Northern California and beyond, who happened to be African American, had raised the question of apartheid back in the late fifties or early sixties. Bill had raised the question, but it didn’t go anywhere. In 1976 it was a different matter. It was a different matter entirely, because I guess you could say that by 1976 the African American population of this country had sort of arrived. We had started to be elected to various offices around the country and had gotten jobs, such as we could be a post person and get a job at the fire department if you really pressed—those kinds of things. But the question of apartheid—once I looked into it, I found out that, number one, the government of the United States had been complicit. And so that upset me. I said as a result of that one of the aims of the anti-apartheid movement should be to expose the complicity of the United States government and to neutralize it insofar as the liberation movements are concerned. In July of ’76 the first of the anti-apartheid resolutions was introduced in Local 10 by myself and others. A little short resolution that simply said that due to the situation in South Africa, we were calling for a boycott of all goods to and from South Africa and Zimbabwe. Plus, the original resolution, when it left Local 10, it went to the International executive board. The International executive board changed the words from “demand” a boycott of South African cargo to “urge,” okay? Which means that we knew then that we had our work cut out for us in terms of educating the membership not only of Local 10 but of the entire international union. We had become part of the labor-based anti-apartheid movement. At the time, we were the first anti-apartheid labor committee in the country. We raised the question of apartheid to the level of visibility within the trade union movement, because the AFL-CIO played its usual role when it came to foreign workers, particularly black workers in Africa. They gave it a oneline, half a paragraph blurb in their annual report. And then committees started popping up all across the country. Starting here in the Bay Area, we started sending out resolutions to the state federation, to the national convention of CBTU [Coalition of Black Trade Unionists], even to the executive council of the AFL-CIO. This is over a period of years that this occurred. Then in 1977 or ’78, we held the first anti-apartheid labor conference in the United States at Local 34 in San Francisco. In April of 1977 we had a two-day shutdown. Myself and the committee had made arrangements with the chief dispatcher that the community people were going to come down to Pier 27 to protest that ship, the South African cargo. So we made sure that Local 10 members who were sympathetic took those jobs, knowing that they were not going to work. And so for two days we tied them up. We tied that ship up. That was the first of many demonstrations at the docks. The one that got the most attention was in November 1984. By then we were better organized and the whole question of South Africa had become an issue nationally. They were calling for the release of Nelson Mandela. They were calling for entertainers, black entertainers, to boycott South Africa. Because by then Sun City was up and running in South Africa and they were inviting black entertainers from the U.S., offering them huge sums of money to come to Sun City to entertain. And we were saying to them, don’t go. If you do go, demand to speak to Nelson Mandela. Otherwise, don’t go. Ronald Dellums

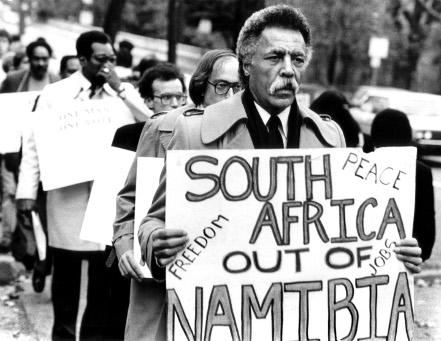

Congressman Ron Dellums of California protests in front of the South African embassy, December 1984. Photo © Rick Reinhard. Ronald W. Dellums of California served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1971 through 1999, representing the district that includes Berkeley and Oakland. He grew up in Oakland, the son of a longshoreman who was a member of the same union as Leo Robinson. His uncle was a protégé of national labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph. Working as a social worker after a short stint in the Marine Corps, Dellums was urged by community activists to go into politics, and he gave up plans to pursue a PhD. Elected to the Berkeley City Council in 1967 and then to the House in 1970, Dellums regarded himself as “a voice for the movements” in Congress (Dellums 2000, 2). He was one of a group of urban progressive legislators who, in his words, worked inside the system and learned its rules while relying on the “street heat” of activists to command the attention of those in power (5). In his memoir, published in 2000, Dellums dedicated a chapter to the years of campaigning on apartheid. “The liberation of South Africa from the yoke of apartheid is one of the most important political and human rights events of my lifetime,” he wrote, “and I consider having played some role in it to be my greatest legislative and personal achievement” (6). The following excerpt is reprinted by permission from Lying Down with the Lions: A Public Life from the Streets of Oakland to the Halls of Power (Boston: Beacon, 2000), 121–40. A group of workers from a Polaroid plant had come down from New England [in 1971] with the express purpose of meeting with members of Congress to discuss their concerns regarding their company’s commercial engagement with South Africa. The [Congressional Black Caucus] chairman, Charles C. Diggs, Jr. (D-Michigan), asked me to meet with the Polaroid workers and report back on their concerns. [John Conyers (D-Michigan) joined me, and] we agreed to receive their petition and to take up their cause within the Congress; we also promised to use our good offices to bring their case for sanctions against South Africa inside the system in any other way we could. . . . By February of 1972 we had introduced a disinvestment resolution for consideration by the House. . . . In fact, it would be more than a decade before the Congress was prepared to come to grips with ending U.S. complicity in the perpetuation of the apartheid regime. . . . But our resolution provided a vehicle for those on the outside to use to begin to build pressure on the Congress for legislative action. In 1985 we were prepared to press for a vote on our bill—thirteen years in the making, and by now a rigorous and demanding bill. . . . Throughout the early 1980s, my office was in regular communication with the liberation forces in Southern Africa and with activists throughout the United States. Damu Smith of the Washington Office on Africa became one of our closest political supporters, in on the ground floor and working tirelessly on behalf of our effort to achieve a complete economic embargo of South Africa. . . . At the same time, Representative Bill Gray sponsored an alternative approach, the focus of which was to prohibit new investment. The antiapartheid movement was split on appropriate strategic next steps in the legislative arena. Some believed that they should strike to the center, support a more moderate bill and seek the “achievable” outcome; others wanted to press for maximum sanctions. In addition to introducing a bill that reflected my own preference for the latter course, I had also co-sponsored the Gray bill, along with my CBC colleagues, in an effort to ensure that some action by the United States would be taken. In 1985 neither bill became law, as President Reagan threatened a veto while issuing an executive order imposing very limited sanctions. The next year the Gray bill moved through the House of Representatives, as it had in 1985. At the end of the debate, the House voted on an amendment . . . substituting the stronger version. At that moment there were more Democrats on the floor than there were Republicans. Those colleagues who surrounded me on the Democratic side wanted to voice strong support for our effort—and the ayes rang out loudly. They clearly overwhelmed the more tepid nay votes that arose mostly from the Republican side of the aisle. The Republicans made a tactical error in failing to call for a recorded vote that would probably have defeated the amendment. Representative Mark Siljander (R-Michigan) [said] that they calculated that the vote would fail in the Senate, and would be seen as too radical. But I sensed that in fact Siljander had loosed a tidal force by failing to call for a recorded vote. I had seen that no Democrat had the heart to oppose the disinvestment bill. It was also apparent that Republicans were reluctant to be seen as favoring apartheid. They were all caught in a conundrum. The bill thus passed the House, but the Senate passed a weaker version, and the House Democratic Party leadership accepted a compromise to put forward the weaker Senate version to President Reagan for signature. In the end, Reagan’s veto made a Senate bill that I and other activists felt was a weak one far more significant than would otherwise have been. When the Republican Senate and the Democratic House both overrode the veto, a clear message was sent to South Africa—the people’s representatives within the government of the United States had trumped the executive branch, and had taken control of the character of the sanctions that would be imposed. Our three-pronged strategy had worked: first, consult with grassroots activists and provide them with the grounds from which to press in congressional districts for the most principled position possible—in this case, complete disinvestment and embargo; second, work with willing national organizations to generate a lobbying presence on behalf of bold government action—maximum sanctions, in the case of apartheid—always creating pressure to move the middle to the left; third, engage congressional colleagues and educate them about the issues and the pathways for change. |

This page is part of the No Easy Victories website.